Tips on Creative Research: Good Research Lets You See Your Story

“Sometimes it’s not enough simply to peer intently into your own soul. Sometimes you have to look out the window and see the world in all its complicated glory.”

—Philip Gerard; The Art of Creative Research

I remember asking, “What is a trimester?” I blushed when my high school teacher answered me. My ignorance was exposed! How much more should a writer, whose work has the potential to last longer than a classroom discussion, avoid embarrassment by striving to know what he is asking about? To be fair, I was innocently unfamiliar with the term back then. But when it came time to write about an unplanned pregnancy a decade later for a creative writing project in WRIT 402, you bet I began covering my bases by researching the relevant angles, even if they were only peripheral to the narrative details of my short story. I found that the plainest discoveries in research can ignite and support the most authentic, meaningful handling of subject matter in creative writing.

Enjoy these few tips on navigating sources and weaving them into your creative project.

Why research?

You are a writer, but first an observer. A natural observer first, then a committed researcher. A writer applies and exercises their natural inquisitiveness through methods of research.

Research isn’t just about plucking out facts that are out there somewhere. By finding facts, you are researching your story as you form it. That’s what makes research a creative act.

Creativity asks as much as it answers, and research offers its share of asking and answering. It should be an inviting part of the creative process, leading to the discovery of what’s there and to the creation of what not yet is.

“Write what you know,” many advise. It is probably worth adding that we can only write what we know. To write more, we must learn more.

You are writing about something because you care about something. When you choose to write, you owe it to yourself and to your readers to know what you are talking about, to expose yourself to relevant materials on your subject so you can internalize and embed truth into your work with credibility and authority.

For my creative short story in WRIT 402, my plot background is backed by real lives I learned about through research. My plot imagines plausible characters and situations that I can support and defend from the content I absorbed in my research.

In a nutshell, research gathers facts about what things are and how those things relate to other things in the world.

Facing the facts

Facts live before they’re told. They often follow the tracks of a story. Art may imitate life, but life is really the only art there has ever been. Experience is the pen’s early ink.

The sources I gathered for my project ranged from journalists and researchers, health experts and credentialed specialists, to individual testimonies. This gave me a wide range of contexts to pull from. Some of these authors researched their topics from arm’s reach. Others had faced the ferocity of their topics firsthand.

It is good to diversify your sources. One of my sources summarizes a topic from a broad view with many historic perspectives, while another source comes from an author who had personally lived through the topic and gained an uncompromising view. Each kind of source carries its own voice and authority, which can add depth to your own.

You notice different things from different vantages, whether from afar or up close. You can verify one source by comparing it with another. You see continuity emerge. You see the shades of it from all the relevant angles. The light shifts on it from source to source, making a composite impression. Whether colorfully vivid or colorless in the dark, it remains the thing that it is. Everything comes into focus, giving you confidence that you understand the material well.

You probably can’t know everything about a topic. But you don’t have to. You’ll find no end of rocks to look under. But the rocks you do look under you can carry with you.

Look at what’s around you and seek it out. Set your focus and commit yourself to understand what you find.

So how do I find and use my sources?

Sources I gathered for my creative writing project in WRIT 402 included digital media and traditional print literature.

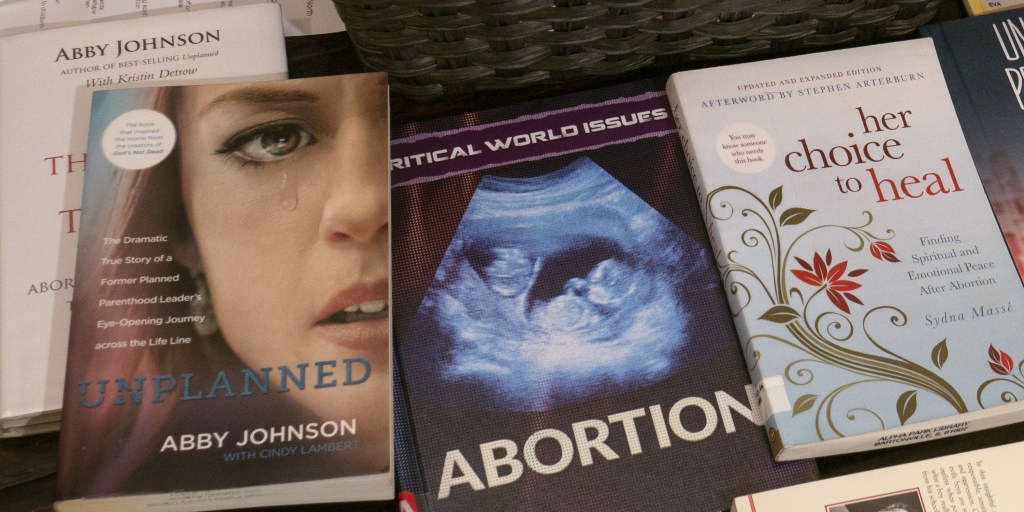

I found my print sources by searching through my local public library system online with topic keywords and authors on my subject. I tried entering different terms and combinations, finetuning searches to yield helpful results. After scrolling through dozens of items in the system, I selected several books and had them delivered to my local library for pickup.

In addition to public libraries, academic databases are usually available to college students. They include professional journal articles as well as published books and other items that you can find online or on campus. Consider every research option that may be available to you. I should also mention that I supplemented my library use with online access to materials through Hoopla and Google Books.

In the digital age, a lot is available besides print literature. Several podcasts, webposts, and a university lecture webcast were integral to my research. So was an analog pocket radio, too! Your topic lives in many bandwidths.

You hear people say, “Oh, I saw it on the internet.” But that answer says nothing about where they actually saw information. Online material is made up of webpages that are uniquely identifiable just like published literature, encompassing a massive variety of formal and informal content. Many online sources helpfully cite the sources that they use. The Modern Language Association of America offers good criteria on how to identify sources on their Works Cited guide and elsewhere.

How do I know what’s credible?

Published works are generally vetted for quality before going to print, and nonfiction books often provide their sources in footnotes or a bibliography in the back of them. You can cross-reference information, drawing comparisons in their logic and thought-forms, rubbing sticks together to make a flame.

Bias—a particular stance for something—isn’t necessarily a bad thing. You just have to know when it’s there, what to do with it, and how it relates to your subject as a whole.

Whether online or anywhere, look for competence and a sense of ethical trust. In my research, I discovered The Seth Gruber Show as a solid source thanks to the daily Moody Radio program, In The Market with Janet Parshall.

Contested ‘arguments from authority’ hinge on what’s inside. Critically read between the lines while also trusting them, letting your sources earn your trust. Truth is there, whether buried or unsurfaced. So put your sensors out. Investigate the material that is touching your topic.

Living with the facts

Let your research speak to you, but also speak to it. Decide when to let it guide you and when to guide it by guarding your focus. Discern when your attention should linger or move on. You may find that you will spend more time on some sources than others.

Some sources were a guiding center for my story while other sources helped round out the edges. I spent most of my time on those sources I found to be the most important to the narrative details of my story. But they all were beneficial to me in some way.

You do not have to read every word of your research contents. I sure didn’t. Holding a book in your hand for a few minutes can do a lot for you, giving you a solid impression of the subject. If you can’t read everything, you can at least look at chapter headings and skim key passages. Or you can spend a whole night reading a book cover to cover if it’s crunch time. Pace yourself however is best for you and your project. Learn as much as you feel you should. Honor your sources by taking the time to really understand them, to live and ‘talk’ with them.

Examples of writing from research in my short story

Research can confirm your preconceived assumptions about your topic or offer nuanced redirection.

“A teenager who finds out that she is pregnant may want to terminate a pregnancy because she feels that she is too young to have a baby,” says the research writer of Critical World Issues: Abortion (Walters, p. 53). That is exactly the rationale for why the protagonist in my story admits, “I wonder about abortion.” My protagonist then explains what she expects from life at that vulnerable time.

Pictograms of fetal development from conception to birth appear in a chapter on “The Question of When Life Begins” (Walters, pp. 29-31), encouraging a line in my story about how millions of sperm cells “raced to become a zygote, then a fetus, then you and me.” My next sentence, “There’s another heartbeat inside you even now,” is affirmed by an article from Medical News Today that considers when a fetus’ heartbeat is detectable.

Before I read Abby Johnson’s groundbreaking book, Unplanned, I assumed abortion clinics never showed ultrasounds to women. But a discovery in her book corrected me. At the abortion clinic Johnson had directed, most women declined to see an ultrasound (Johnson and Lambert, p. 46). So that meant some abortion clinics do show ultrasounds. This led me to rework some dialog in which one character begs my protagonist to see an ultrasound while indicating that there are medical alternatives like the Destiny for Women Health Clinic and Empower Life Center in my hometown, Peoria, IL. This research discovery also led to one of the subtlest moments of sharp emotion later on in my story.

The facts you find in research go hand in hand to form the emotional thrust of your story.

Fact and form

So, should you mention everything you learn from research in your story? No, not every detail is going to make it in, but everything you do learn contributes to your mastery of the subject. It sharpens everything you do include. Experienced writers will tell you: It is good to know more than you have to use. Our eye hits a focal point, yet everything around it is what makes up most of our vision. That’s the periphery of things, and the quality of researching for writing.

Do I mention as fact in my short story that abortion is known to occur in virtually every socioeconomic demographic? No, but I do narrate the lives of a struggling teen from a bad home and an accomplished university professor who’d both faced unplanned pregnancy in late-modern America. Facts add up to form the whole. They’re how a scene and situation gain life and substance in your story.

The filter that separates truth from error in your work should be you, the author. Research is a responsibility. It is discernment and care. Listen to the facts you find. Hear how they breathe along with your ideas. You can create something honest and credible when you are honest to your intuitions about the topic while caring about others who’ve experienced the topic.

If you are writing fiction like I did, you can include an Author’s Note at the end of your story to credit your sources and describe how they helped inspire you. Just be careful that your work is original. It should be your story. Your story simply shares the same universe of others’ experiences, especially if you’re writing for realism like I did.

It is up to you to find out how research can weave in and out of your ideas, to strengthen the integrity of your ideas, growing who you are as a storyteller.

Writing is the great challenge of peering just past the horizon while never dashing too far from home. Your discoveries may only be as far away as your local library or someone knowledgeable you know who can speak into your topic.

Research is a necessary and exhilarating part of the creative process for any creative writer venturing to write about things that matter. Step out. See what’s out there and inside you.

Links

- Hoopla | Containing thousands of books and other media, this resource is free and connects to the public library system.

- Google Books | Google Books is useful for previewing content online, reading synopses, and getting a feel overall for a work in digital print. Most published books can be found here.

- Works Cited: A Quick Guide | The Modern Language Association of America, commonly known for its MLA style, has been an academic authority on writing for over 140 years.

For Further Reading

The Art of Creative Research: A Field Guide for Writers by Philip Gerard (University of Chicago Press, 2017). Practical and poetic, this book is a step-by-step guide and a memoir of sorts on writing research. A great read that relishes the shape and approach of one’s writerly identity in the field.

The Christian Imagination: The Practice of Faith in Literature and Writing by Leland Ryken (Waterbrook Press, 2002). A moving collection of insights and essays from some of history’s greatest writers. “The more we learn about ourselves, the deeper into the unknown we push the frontiers of fiction,” wrote Flannery O’Connor.

Works cited in this post

Anna Smith Haghighi. “When does a fetus have a heartbeat?” Medical News Today. 29 Jan 2024. Healthline Media UK, 2024.

Abby Johnson and Cindy Lambert. Unplanned: The Dramatic True Story of a Former Planned Parenthood Leader’s Eye-opening Journey Across the Life Line. Tyndale House Publishers, 2014.

Philip Gerard. The Art of Creative Research: A Field Guide for Writers. University of Chicago Press, 2017.

Mike Walters. Critical World Issues: Abortion. Mason Crest, 2017.